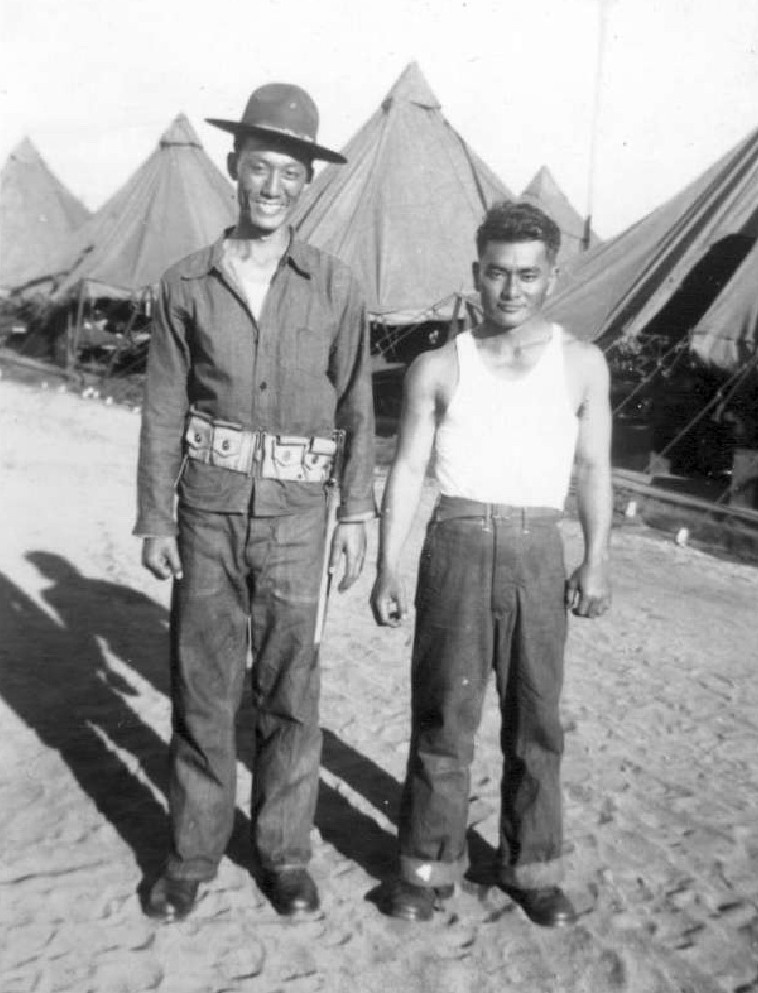

Charles Sue and friend, 25th Infantry Division, Schofield Barracks, Territory of Hawaii, probably circa early 1942. |

includes Asian Americans

As a child, the 1950s was a peaceful, idyllic time. I remember family gatherings in Hawaii with aunts, uncles, cousins, and Ahpo (grandmother). World War II was over. Standing in the shadow of that cataclysmic event, my cousins and I failed to appreciate the sacrifices of our parents' generation. I've since come to appreciate that generation more. Recently, my uncle, Charles Sue, 94, began recounting some of his World War II experiences. A Saturday night spent with my Aunt Wilma at Hanauma Bay morphed into a historic Sunday morning, filled with the sound of distant explosions and the sight of black smoke and Japanese airplanes. It was December 7, 1941. When my cousin Gwenne was interviewing her father for me, Charles told her that my other uncle, Robert Hiroshi Koreyasu, was a combat veteran of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team that had fought so valiantly in Europe. The 442nd suffered 90 percent casualties and two of those were Hiroshi's buddies. My God! After all these years, I hadn't heard one peep from my uncles. They were heroes from within my own extended family! That generation didn't brag about their exploits. |

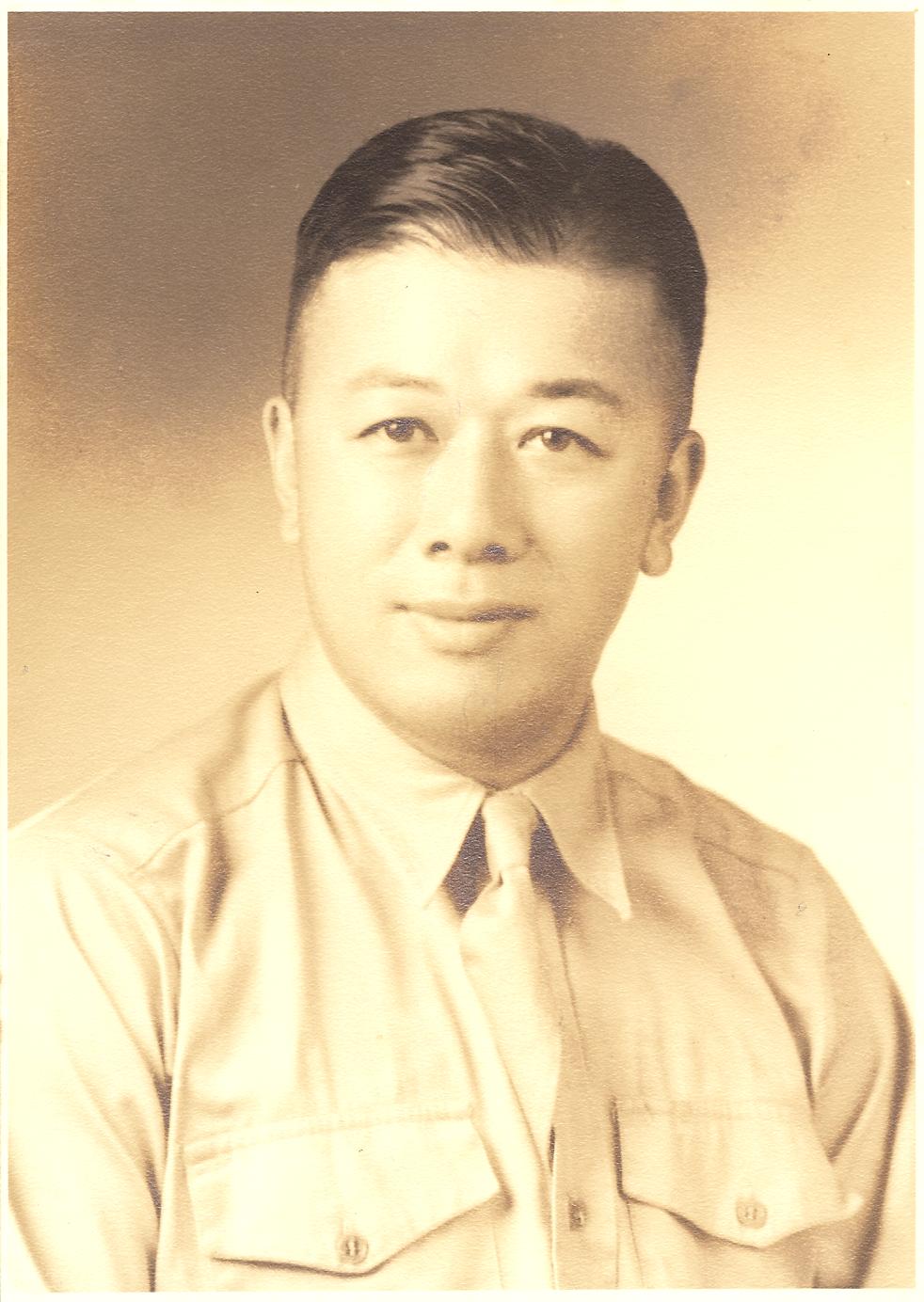

Robert Sue, the author's father, 298th Infantry Regiment, Hawaii National Guard, incorporated into the 25th Infantry Division (photo probably circa early 1942). |

The Japanese Americans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team are famous for their deeds in WWII, but very little has been said about the Chinese Americans who served. Some formed a small minority of the 25th Infantry Division, which was activated on October 1, 1941, at Schofield Barracks, Territory of Hawaii. It included the 65th Engineer Combat Battalion (Uncle Charles' unit) and the 298th Infantry Regiment of the Hawaii National Guard (my father's unit). My other uncle, Tony Ah Choy, 92, served in the National Guard, defending the home islands. My father (Robert Sue) and Uncle Hiroshi are deceased, and a wealth of stories are lost. But, my father did recount one of his experiences on Guadalcanal. The Hawaii boys had caught and confronted a white soldier who had stolen some of their belongings. The white soldier pulled a knife . . . and that is all I remember. I was to join the Marine Corps soon, so it was an anecdote suggesting that one should not only beware of the enemy but perhaps some fellow troops too. Uncle Charles' unit was part of the 35th Regimental Combat Team sent to relieve the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. He remembers spending a month on the high seas, seasick, dodging Japanese subs and dropping depth charges when they detected any, and doing endless calisthenics. Their refrigerated food was tossed overboard because it had spoiled, and the troops subsisted only on coffee for a period of time. They landed in New Caledonia (off Australia) for 1 to 2 days to replenish supplies. On Guadalcanal, the combat engineers were used as regular infantry, and their team drove the Japanese from the central part of the island to Cape Esperance. During this time, he developed yellow fever with a 105 degree temperature. They subsisted on #10 cans of chili con carne. The Japanese had snuck Chinese from Manchuria into Guadalcanal, for slave labor. Charles remembers one of them following his unit like a dog, so happy to be liberated from the Japanese. Guadalcanal was secured by them in February 1943. Then, he took part in the rest of the Solomons campaign, including New Georgia Island. He spent 167 consecutive days in combat. Afterwards, his unit had rest and training in New Zealand and New Caledonia, in preparation for the invasion of the Philippines. |

The author’s other uncle, Robert Hiroshi Koreyasu (circled), Regimental Headquarters Company, 442nd Regimental Combat Team. From The Album, 1943, Atlanta: Albert Love Enterprises, 1943, and www.katonk.com. |

The 25th Infantry Division, now assigned to the Sixth Army, landed on the shores of Lingayen Gulf, Luzon Island, Philippines, in January 1945. The men had to discharge the cargo. Charles remembers having to march, while towing the 6.4 -ton, 155-mm howitzers, to a small town called Binalonan. They continued to San Jose, where in a brief respite, he cut Henry Chung's hair. Life was very primitive, with no running water. They had to drink from the village wells. They did not interact much with the villagers, he recalls. The 25th Infantry Division suffered the highest casualty rate of any division of the Sixth Army during this campaign. |